Archive for the ‘Review’ Category

Reading discoveries: The Martian

For the last year I have had a professional task which I have found almost impossible. It has made me think about writing in quite a new way. And also about how much the reader always brings to a book. For a first read, the writer is a sort of tour guide to the author’s interior landscape and the world of the story. But what the reader takes away is so much more than what the guide actually says. It depends on the reader’s habits, tastes, experience, expectations and even previous reading.

This month I found The Martian by Andy Weir. I fell over it by chance, browsing. It’s science fiction, a genre I like rather than love and by which I am often disappointed. This one was brilliant.

I ended by sitting up until 3.45 am to finish it because I couldn’t go to sleep without knowing the end. But it was about so much more than the ending. It sets up a series of dilemmas which mostly seem irresolvable until a cast of believable characters apply brain, body and will. The stakes are life or death right from the start — and then they escalate! The sciences — physics, chemistry, thermodynamics, even agriculture – almost become characters. One by one they are tested and may or may not betray our hero. I was on the edge of my seat, not just at the end but again and again throughout this thrilling book.

Now I need to buy a physical copy; e-book is not enough. This is one I will re-read, probably many times. Why did I LOVE it so?

Well, excitement, obviously. It’s a cracking book by anyone’s standards, written with passion. Andy Weir sounds an interesting guy from his interview, a self-proclaimed nerd who initially self-published his book of the heart. He might not call it that, of course. But note: he says ‘The deeper into the book I got, the more excited I became.’ Yup. Been there. Bliss. And it leaks out to the reader, believe me.

But what did I, the reader, bring to the experience? Me, non scientist, non nerd? I’m even terrified of changing from Windows XP, for God’s sake.

Though I did enjoy physics at school. And, of course, I plant stuff and sometimes it grows. That’s two things I share with The Martian. I like the way he goes about it, too. He evaluates, considers his options, works out an idea in principle, refines it. Yes, I do that. Sometimes. Then he puts his plans into practice in an orderly way. Um no, I could learn from him there. And he’s attractive. He feels all the things that I would feel but he doesn’t panic. And he’s heroically fair and philosophical. I find both pretty sexy.

In fact I once asked a group of romantic novelists which was the quality they most loved in a hero: looks? wealth? power? sophistication? biting wit? fond-of-dogs? ‘Competence,’ said one. Ah yes. We all went a bit dreamy. Well, the Martian is definitely the sort of guy who could put up a shelf and start the car on a cold day, if that’s your preferred lust object.

And I have been in love with one of the Martian’s literary ancestors for most of my life. In Victorian England a retired Naval Officer called Marryat wrote a book for children about a family of Royalist orphans who were rescued and hidden by their gamekeeper after the Battle of Naseby. Marryat was definitely a Cavalier by inclination and his hero is undoubtedly the hotheaded eldest son. But I loved his younger brother, Humphrey, who works out how to damn streams, catch eels and generally make life manageable and, above all, interesting.

But then, in reading The Children of the New Forest, I had already picked up the 1066 And All That view of the Civil War – Cavaliers, wrong but romantic; Roundheads, right but revolting. And to be fair to Marryat, he does manage one decent Roundhead, at least.

The world of The Martian is Roundhead-free. Nor is this science fiction with monsters and aliens. This is about real people. Lots of them. Yes, our hero is on his own. We tune into his interior monologue, all of it, including the stuff he doesn’t tell anyone else, even when he can. It is like being in our own heads. But there’s all the other people involved. There they are, wheeling remotely like the rings of Saturn – close colleagues, family, Management which could make a story in itself) along with office politics, media politics, even, at one point and very convincingly, international politics. The decisions in this book are not wholly the Martian’s. Other people’s plans are crucial to his survival. And everybody makes mistakes.

So there’s

- exciting plot

- author persuasiveness (bit mealy mouthed but can’t think of another short way to describe it)

- fabulous hero

- world of the story

- AND? – well, humanity.

The Martian has a generosity of spirit about his fellow man, as we learn in the first couple of pages, while he’s calculating how long he’s got to live. Mostly he’s not wrong. It makes for a mind-blowing climax.

Great character. Great book.

COX – Reflections and Review

I have to admit that I was an Olympic skeptic. There are many reasons for this but I put its origins down to childhood trauma. I had a serious sportsman for a father.

Back in the last century he went to Berlin to represent the UK in an international table tennis duel which produced an ode from the then Manchester Guardian to: ‘Five stalwart Englishmen, crossing the stormy ocean, To ping and to pong in Britannia’s name’. My mother cut it out and kept it. They broke up shortly afterwards. It took several years and a World War before he forgave her. And, notwithstanding his being a lifelong Labour voter, I never saw him buy or read The Guardian. Though, of course, that could have been down to the quality of the cricket reporting, which was what forced him into the embrace of the Torygraph, an organ whose leaders regularly reduced him to apoplexy at the breakfast table. He also ran various distances, played cricket, hockey, tennis, squash and God knows what else.

You will see that ours was a conflicted household. Sport was at the root of most of it.

As a result, show me a man in sports togs with the gleam of battle in his eye and I take a swift side step and head for the hills until it’s all over. Romantic hero? Nah, not a chance.

Kate Lace has changed all that.

Now, I’ll be honest, she’s a mate of mine, so I was always going to read COX. And she’s a good writer, so I expected to enjoy it. Did I expect to be swept away, horizons widened, world view changed? Well, no. Yet half way through reading it, there I was, watching the Olympic rowing– punctuated by her excited tweets — live, with my heart in my mouth. And, I’ll admit, the occasional tear in the eye too.

This is, quite simply, a lovely book. We follow a group of young rowers through their local or college clubs, to national trials, culminating in the Olympics themselves. The punishing training regimes, the costs of backsliding, the sheer physical strains of the race itself, even when you’re in peak condition, are fantastically vivid. And I never once disengaged, in spite of a lifetime of avoiding this stuff, because Kate Lace absolutely made me buy into the world of the story and care what happened to her cracking cast of characters.

There are the hunks, of course — dark, brooding guy works his way through college and is innately hostile to rich, careless, manipulative sex god working his way through anything female; and the gorgeous girls. And also, the quite nice, ordinary girls and the guys who don’t make the cut and still have a pretty good time anyway. They have flaws. They make dreadful misjudgements, about themselves and what they have to do to stay in the game. Earning a living isn’t always easy. And nor is keeping a relationship going when you’re really focused on your sport. You really feel for them. They also shag a lot and without benefit of whips and chains which, in the current literary climate, is a real pleasure. You have a huge sense of completion (and a couple of bonus rewards) at the end of the story.

Above all, it’s a load of fun. I hooted aloud more times than I can say. And I love the minor themes that run through the book, like the couple who are regularly surprised under tables in flagrante. Did I say, these guys shag a lot? Well, they’re in peak physical condition so it’s only to be expected.

What is so clever is that what these rowers achieve and what they mess up can be translated across just about every field of human endeavour. For instance, there is a spine-tingling account of how you can work in absolute harmony with someone you think is pure poison; and a woman who wants something so badly that she won’t try for it in case she misses, which made me wince with fellow feeling- as well as wanting to slap her; and the laughter and fellowship which get you through the good stuff and the bad.

So thanks to COX, I braced up and watched a race (or five or six), even though I knew most people were going to lose and it always makes my heart ache for their disappointment. And by golly, it made me respect our sportsmen and women. I whinge because I labour mightily over a book for months and months and then someone comes along and tells me she finished it before the bathwater got cold. Yet these guys put their whole lives on hold for four years while they train for the Olympics and their chance to show what they can do is over in minutes, even seconds.

This is definitely a book to read by the pool with a large drink or three. Or on a crowded train. Or anywhere, really. The world will hold you and the characters will take you with them and maybe even change you a little. And you’ll have a ball.

The Cornish House – Review

Back in May I went to a very jolly party, with Cornish pasties, in Waterstone’s Kensington High Street to launch Liz Fenwick’s debut novel, The Cornish House. Since then I have read it twice and followed with fascinated admiration her blog about getting on the road to promote her book. Her energy and good humour about this daunting part of an author’s life are an object lesson to a lot more of us than debut novelists, believe me.

The novel has made me think. I gallopped through it on holiday, in between prowling rain-soaked bits of countryside in company with a Birdwatcher. (Actually that sounds a lot grimmer than it was. The air was like champagne, even when the sun was hidden behind a roof of storm clouds, and brief bursts of intense sunlight illuminated the landscape like a mediaeval Book of Hours.) It was definitely a book where I wanted to know what happened next — and some of it I really didn’t see coming, which is why I am walking on eggshells here not to reveal any spoilers.

But the first gallop left me unsatisfied. I wanted to read it again. Now I have and it was worth it.

Maddie Hollis is thirty-eight, childless and a new widow with an adolescent stepdaughter, Hannah, for whom she is responsible. When the novel opens Maddie’s husband, John, has been dead for 6 months and she is moving to the Cornish house of the title, which she has inherited unexpectedly from someone she has never heard of. The house is neglected, Maddie is short of money and needs to start earning again (she is an artist) and her stepdaughter is foul-mouthed and furious. Enough, you would think, to make Maddie hit out in all directions. But, as Liz Fenwick movingly depicts, Maddie feels empty. And she’s having nightmares from which her own screams awake her. ‘Grief was supposed to lessen with time. That’s what they’d told her but, instead of fading, each night she was haunted more than the night before.’

This is a book which sets its own rules. Just at the point at which I was thinking oh no, not another death, this could beat Midsummer Murders at its own game, I realised that the recurring doom in every story Maddie uncovers about people from the past absolutely reflects her own grief. Good things do happen — there is not one hunk but two, both of them interested in Maddie; locals welcome the incomers and are consistently kind, teasing and inclusive. She responds, and so does Hannah; but only fitfully. There is even a moment when Maddie has to suppress jealousy over the closeness of her sprightly neighbour and her husband. It rings painfully true. There are seasons to mourning, as there are to the year (and Liz Fenwick is very good on the changing Cornish landscape over the months of this story), and they can’t be hurried, even though dealing with a poisonous teen, the pub and picnics still have to go on in another space in Maddie’s head.

There is much that is life-enhancing, too: the run-down house, with its mysterious corners, the social life of the village, its continuity over the centuries, Cornwall itself. Even Maddie’s emotional turbulence is vivid evidence of the world turning: grief makes her heroic, problem-solving, opens her mind; it also plays hell with her judgement and turns her intermittently indecisive and obsessed.

Trying to give you a flavour of this book, I came up with somewhere between Daphne du Maurier and Miss Read. There is du Maurier’s love of Cornwall and her sense of the chaotic, exhausting power of emotion. But du Maurier darkness is alleviated by Miss Read’s gloriously normal gossip, feuds and neighbourly interference for good or ill.

Above all there is kindness, both trivial and profound. Ultimately this is a hopeful book– and also a healing one.

Romantic Novel of the Year 2012

On Thursday the UK Romantic Novelists’ Association presented the RoNA to Jane Lovering for Please Don’t Stop the Music, published by British independent publisher Choc-Lit.

On Friday I read it. It had previously won the romantic comedy section of the awards, so I thought I knew the ball park. I was wrong.

It has the tightly knit cast of friends (and the odd foe) that we have come to expect from romantic comedy, some of which is sometimes called chick lit. It is witty, perceptive, with some very good one-liners, including the opening sentence: ‘You know you’re in for a bad day when the Devil eats your last HobNob.’ And at that point it waves goodbye to Bridget Jones and her mates.

The important thing is that these girls have no safety-net. You look in vain for the aged Ps, who need to be placated or avoided but ultimately may provide a refuge in the shape of childhood bedroom and in-before-midnight. There’s no flinching away from the smug marrieds, no partner hunting, not a randy boss or backstabbing colleague in sight, no alcoholic clubbing after work. These people are self-employed and hanging on by their fingernails to a roof over their head. Welcome to Cameron’s Britain. They’re problem solvers, they help each other out, but it’s not an easy life and they don’t know everything there is to know about each other.

You feel that, even as your guide and heroine, first person narrator Jemima Hutton, takes you on a brisk, witty, courageous tour of her life. That’s her life now. Because Jemima has secrets and she’s not the only one.

The plot, and it is a good one, is rooted in those secrets and I’m not giving them away. I’ll just say that the hero is gorgeous — and it takes Jemima a surprising amount of time to notice. I got there the moment she mentioned his jeans. And he’s got a lot of baggage. Jemima herself could give the Duchess of Malfi a run for her money in the tortured backstory department. The local habitation is York, brilliantly evoked. And the happy ending resolves really big issues believably.

Jane Lovering’s voice is lively and the book positively swoops along.

I read it in a sitting. Enjoy!

Three Spies and a Kindle

Getting to know my Kindle better, I downloaded No 4 on the Spies and Thrillers chart, The Fulcrum Files by Mark Chisnell.

Set in 1936, it’s a story rooted in a period when people were desperate to believe that 1914-18 had seen the war to end all wars, when communism offered an apparently viable alternative way of organising society and the increasingly confident Soviet system was setting up networks to export it. In Britain, manufacturers were almost as reluctant as the government to believe that Germany was re-arming, as Mark Chisnell points out in his PS to this exciting story. It is also a time when pacifism was a vibrant issue and deeply divided friends and families.

Chisnell’s hero, Ben Clayton, is a decent upright human being, a bit of an outsider because his education is above his social class, and even more of a loner because, for profound personal reasons, he is a pacifist. The plot is convincingly riven with class warfare, bully boys and heroism, as our hero tries to investigate an accident with a newly designed mast in which his friend dies. He also tries to look after the widow, be straight with his girl friend (a lovely character) and keep his job. By the time he finds himself on the run in Germany, trying to keep ahead of the Gestapo, I couldn’t put it down. And there is some of the best writing about a chase at sea that I have read since The Riddle of the Sands, a book which our hero has read, marked, learned and inwardly digested. Riveting.

The Riddle of the Sands, published in 1903, is possibly the first spy story. I read a little John Buchan as a child and Fleming as I got older and could take it or leave the genre, frankly, though on the whole I preferred to leave James Bond. I didn’t find The Riddle of the Sands until I was in my twenties and living in Ireland.

Childers was a real child of empire who was converted to the cause of Home Rule and died gallantly for it in front of a firing squad in 1922. (His son was 4th President of Ireland 1973-74, succeeding his father’s friend Eamonn de Valera.) Childers was an enthusiastic sailor and his most famous story tells of a sailing holiday in the Baltic when a young chap from the Foreign Office (the proverbial Carruthers) is invited on a sailing holiday, with perhaps a little duck shooting, by an acquaintance, Arthur Davies. Davies, in fact, suspects that there is a secret German fleet being assembled off the Frisian islands, preparing to invade Britain and is out to prove his theory. Carruthers, the novel’s narrator is at first disconcerted, then flings himself into the venture and they end up sailing for their lives through the fog to warn England. Cracking stuff. Still on my bookshelf.

In an article in The Spectator in 1955 Ian Fleming criticised The Riddle of the Sands for a lack of believable villains. (So Drax, Goldfinger and Dr No are believable, I hear you cry). He also didn’t think it was thrilling enough! But then I’m not sure that Fleming understood suspense, as opposed to sadism, unlike Childers and Chisnell. But then, I’ve only managed to finish two.

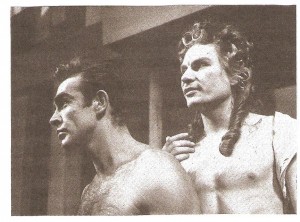

James Bond is now identified by the movies rather than the books and, particularly,by the actor. It is said that the various incarnations reflected their times: currently Bond is an impassive hard man, played by Daniel Craig. Brosnan was sophisticated and witty; Timothy Dalton, sophisticated with a hint of a secret sorrow; Roger Moore a sophisticated comedian; George Lazenby not quite sophisticated — and then, first of all, there was Sean Connery. Fleming had envisaged Bond looking like himself (start with the sneer and work backwards, I guess) but he has a character say that Bond reminds her of Hoagy Carmichael. So this is what he wanted:

What he got was Sean Connery.

Serendiptiously, I came across a photograph of Connery as Pentheus in The Bacchae the Oxford Playhouse, in 1959, his pre-Bond days. (Michael David was Dionysos.) The photograph was taken by surrealist painter Oscar Mellor, who day-jobbed as a photographer with, I think you will agree, spectacular results. (A letter entitled You Muddy Fools appeared in the London Review of Books in 2002 on this self-effacing eccentric.)

Pentheus, of course, was torn to pieces by maddened women. For spying.

An Old Love

This week I went to the National Theatre’s production of She Stoops to Conquer. It broke my heart.

What I saw was a crass, shallow, crude peepshow of a play. Brutish Tony Lumpkin tells two wimpy London fops that his stepfather’s old fashioned house is an inn. So they turn up, give orders, treat their welcoming host as an over-familiar innkeeper and decide that his daughter is a barmaid.

This is a School of Big Brother production. The audience is invited to smack its lips lasciviously at the ensuing social and sexual fallout. Audience? Gloating voyeurs would be nearer the mark. I wanted to run away.

This is where I have to point out that the critics were all pretty keen — “a delight” The Independent ; “a mixture of wit and warmth”, The Guardian; ” fresh, spirited and blissfully funny” The Telegraph. And, to be fair, it is beautifully set and dressed.

Susan Kikoler is my guru in all things London theatrical. She goes to everything worth seeing. I consulted her. She hadn’t seen it but was not surprised at my report. She suspected as much from the tone of the reviews — apparently words like “boisterous” and ‘”spirited” are a give away for end-of-the-pier humour. She was not as upset as I was, though. ”It’s a difficult play. I never liked it,’ she confessed.

Ah. I went back to the text.

Susan is right, of course. Tony Lumpkin’s trick could be cruel. Restoration Comedy was full of heartless toffs tricking the unwary into betraying their inadequacies. Even Sheridan has his cold-eyed moments (Sir Peter Teazle’s realisation that his country wife has betrayed him can be heartbreaking, in the hands of the right actor.) But Goldsmith is different. His characters can be pretentious and silly but they are seldom completely self-deluded — even poor old Mrs Hardcastle knows, really, that she is not forty any more. Above all, they are generous. Even naughty Tony. At least I think so.

Now, I have always felt at home in the later Georgian period, tough though it could be (um, embarrasssing photo of self here)

and I have always loved these people.

I love the battle between countryfied ways and town polish. I love the real affection that Squire Hardcastle has for both his wife (struggling with advancing age and a cheerfully rebellious son) and his clever daughter, in spite of being a little too overtly the master in his own house. And, anyway, he isn’t; his servants talk back and he lets them; Mrs Hardcastle runs her own show and he lets her; he even compromises with Kate on her clothes – she can have Town furbelows for morning calls as long as she wears his preferred simple country dress for dinner time. I love Tony Lumpkin, a sort of Tom Jones in the making, a wild boy with his rural mates who knows he’s too immature to marry his cousin but is fair and generous to her in the matter of her inheritance. Above all, I love poor awkward, stammering, boastful, unwary Charles Marlow who, under the gentle encouragement of a well spoken inn maid, manages to find equilibrium between what he feels and what he can bring himself to declare to the world.

And what did I find at the National Theatre? For socially insecure young men, one of whom is a bit of a swot, we had cowardly fops (“beyond camp”, said my Companion gloomily but with justification, “pure Up Pompei”). Instead of the quicksilver mischief of Tony Lumpkin, we had the threatening leader of a gang of rural thugs. For that sound judge of true worth, lively Kate Hardcastle, we had a wind-up merchant channelling her inner pole dancer.

Nasty and not in the spirit of the play, which was first performed in 1773. Elizabeth Farren, the 18 year-old Kate who took the Town by storm in 1777, had a twenty year career playing Portia and Hermione as well as Lady Teazle and similar roles; then married the Earl of Derby. Her demurely pretty portrait was painted by Thomas Lawrence.

What hurts me is that this play is all the more poignant because Goldsmith himself was a mess. Young Marlow’s self knowledge and honest declaration at the end of She Stoops is hard won and it was Goldsmith’s battle, only with a happier ending. For Goldsmith was a gambler, a drunkard, a poor scholar (none of which applies to Young Marlow), a socially inept pock-marked pauper who never settled to a proper career. He busked his way round Europe, earning his bread by playing his flute, and, when he got back to England, was endlessly in debt, in spite of considerable success in his writing. He was vain, jealous and, in person, unpersuasive to say the least– Boswell records Goldsmith’s ill-judged exchanges with other members of The Club, in which he was constantly tied up in knots by the divine clarity of Johnson. Johnson, friendship at war with honesty, said of Goldsmith, “No man, was more foolish when he had not a pen in his hand, or more wise when he had.”

And that’s what I was missing in this production. The wisdom.

After their first disastrous exchange of tangled high sentiments (pure biography, I suspect, poor old Goldsmith!), Marlow gets away and Kate Hardcastle muses, “He has good sense, but then so buried in his fears, that it fatigues one more than ignorance. If I could teach him a little confidence …..” You think, that’s a sensible, affectionate girl who sees into the heart of things. They’ll do all right.

At the end, still thinking her a barmaid, Charles Marlow eventually realises, “What at first seemed rustic plainness, now appears refined simplicity. What seemed forward assurance, now strikes me as the result of courageous innocence and conscious virtue.” You want to throw your hat in the air and cry huzzah. He’s stopped caring what people think about him. He knows what he thinks about her. And what he feels. And he’s right. It is a triumph

So yes, I am in love again. Reading Goldsmith again. Going back to other eighteenth century writers. I suppose if it weren’t for last Thursday, I would not be. So, for that at least, dear National Theatre: thanks guys! I think.