Archive for September, 2009

Divers Englishmen, the Newt Fancier

More about my great enthusiasm, the Greater and Lesser Spotted Englishman.

2) The Newt Fancier (amicus pleurodelinae)

Primarily, though not exclusively a British species, found widely, but particularly prevalent in places of extreme learning, such as Oxford University, the English Folk Song and Dance Society and Lords. Colouration various but a beady eye and extreme concentration are universal characteristics. Very vocal when interest engaged, otherwise silent. Difficult to spot, but once lured out of the undergrowth, unmistakeable. Lives entirely in its own world. Well worth the effort.

Typical specimens:

Augustus Fink Nottle Gussie is a long standing chum of Bertie Wooster. Typical of the species, amicus pleurodelinae, he is retiring and inarticulate, except when strongly moved. Unfortunately, the only thing that moves him is the behaviour of newts, which he studies to obsession level and, more important, to the exclusion of all normal social awareness. Indeed, in trying to woo Madeline Basset, the girl of his dreams, Gussie decides to take a hint from the Newt’s Guide to Courting. Thus he explains to Bertie his intention to attend a fancy dress ball in scarlet tights:

‘In a striking costume like Mephistopheles, I might quite easily pull off something pretty impressive. Colour does make a difference. Look at newts. During the courting season the male newt is brilliantly coloured. It helps him a lot.’

‘But you aren’t a male newt.”

‘I wish I were. Do you know how a male newt proposes, Bertie? He just stands in front of the female newt vibrating his tail and bending his body in a semi-circle. I could do that on my head. No, you wouldn’t find me grousing if I were a male newt.’

‘But if you were a male newt, Madeline Bassett wouldn’t look at you. Not with the eye of love, I mean.'”

‘She would, if she were a female newt.’

You see? Surreal, but Gussie, who lives entirely in his own newtified world, is quite unaware of it. The Mephistopheles venture, of course, ends in tears. Does Gussie learn from that and change his behaviour? He does not.

See Right Ho Jeeves by The Master, P G Wodehouse.

Robert Webb I was not sure about naming a performer, even after Webb’s jaw-dropping performance on Comic Relief as a hair tossing breakdancer. After all, performers pretend. The great truth about the amicus pleurodelinae is that it is without artifice. And it is wholly unaware that its obsessions are not universally shared. However, Marion Lennox directed me to this quite different RW clip, and I am now convinced. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gTchxR4suto

The intensity, that lack of self-consciousness, the sheer beady-eyed lunacy certainly qualifies. Any lecturer from the twenty-fifth century, when he prepares study notes with quotations from Jane Austen to guide his class of Little Green Jelly Fish through their mid term exams, will undoubtedly add ‘a gentleman does not conga’ to the list of Mr Darcy’s bons mots.

He Who Does Not Twitch Twitchers collect lists of birds they have seen. They want numbers. They want rarity. They are, if you like, the collectors-for-collecting’s sake of the bird world; the one night standers; the flybynights. Your true Birder, by contrast, is one who studies, savours, concentrates and delights.

I was once in a small – very small, it seemed to me – boat on a river in Northern Queensland with a Birder of my acquaintance. There were twelve people in the boat, many of them substantial. It was low in the water. The river was known to contain salt water crocodiles. The Birders (i.e. everyone except me) kept their binoculars glued to the branches of tall trees on the opposite bank, looking for rare species. Indeed, I saw a Papuan Frogmouth myself, and an utterly charming bird it is, too. BUT – but, but, but – there were crocodiles in that thar river and nobody but me was keeping an eye out for them. Floating logs approached our boat and I nearly fainted with horror; a low hanging branch brushed my back andthere was a moment of quasi heart attack whichs still sends me all of a doo dah, if I think about it. It went on for hours. When we got to dry land, I could barely speak.

When I mentioned this some time later, the Birder was surprised and just a little bit disappointed in me.

‘You should have been paying attention,’ he said. ‘We weren’t there to look for crocodiles.’

Yup, the amicus pleurodelinae lives in his own world.

Gentlemen, I do not begin to understand you, I think you are barking mad. I count myself blessed that I live in the same world as you. Respec’

The Frivol, the Geek and Writers’ Time

Units of measurement are wondrous things. Someone – it may have been a Cambridge Professor of Physiology, W A H Rushton FRS; or Isaac Asimov; or even Willie Rushton, Great Man of Thought that he was – proposed a unit of pulchritude. If Helen’s faced launched a thousand ships, argued this philosopher, then we can measure how beautiful a woman is by the number of ships her face would launch. One boat launched equals one milliHelen.

Whoever he may have been, this chap steps effortlessly into the Gallery of Frivols. Welcome, friend!

Writers need a unit of measurement, too.

Anthony Trollope, who invented letter boxes and ran a large part of the Post Office, as well as being the author of the Barsetshire and Palliser novels and much else besides (and my very favourite Victorian) wrote for three hours every day. He measured his output. (Don’t we all?) Only he did it not by time or by number of words written. He did both.

As Post Office Grandee, he went all over the country in those stately Victorian steam trains and, in order not to waste time, had a portable desk made and wrote while he chugged along. When at home, he got up at half past five and wrote for three hours. And he wrote at the rate of 250 words every quarter of an hour. Apparently he kept a diary recording how many pages he’d done every day.

Now you make think this is a bit obsessive. Maybe even a touch of the Geek? Imagine what that man could have done with a fully powered MacBook Pro. But by golly, it got the work done.

Because I, too, need to get the work done I propose:

let one Trollope be 1,000 words per hour, a semiTrollope would be 1,000 words in 2 hours; a demisemiTrollope would be 1,000 words in 4 hours. So if you write 1,000 words a day, as recommended by Graham Green and Stephen King both, you could do it at the rate of one Trollope, two semiTrollopes, fourdemisemiTrollopes . . .or even eight semidemisemiTrollopes, if it takes you the whole working day.

Alternatively, a deciTrollope would be 100 words in an hour.

Writers should always have targets. I foresee hours of happy calculation to achieve mine.

Stir my tastebuds, melt my heart

I’m not sure that the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach but it surely is a tried and tested route into a woman’s. As every discerning reader knows.

My good friend and fabulous RITA and RUBY winning author, Marion Lennox, is blogging for the first time, and musing on food and royals in romantic fiction at www.iheartpresents.com She says: ‘You know, writing’s wonderful– I can just close my eyes and think what would I most like to eat, and there it is, on the page. So my would-be princess can indulge in French champagne and lobster patties and truffles and caviar and strawberries tasting of the sun….’

So true. And your readers can indulge right along with her.

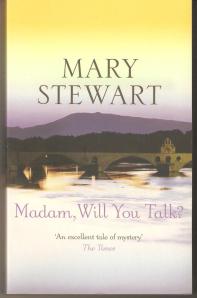

I always remember the first Mary Stewart I read, Madam, Will You Talk.

Cover for the new edition by Hodder & Stoughton 2005

For two days the heroine runs away from a dangerous man who she thinks is a villian. And then, suddenly, he is beside her on the quay in Marseilles and there is nowhere left to run . . .

So what does he do?

He takes her to dinner. (That’s my kind of dangerous man.)

And what a dinner.

I remember still those exquisite fluted silver dishes, each with its load of dainty colours . . . there were anchovies and tiny gleaming silver fish in red sauce, and savoury butter in curled strips of fresh lettuce; there were caviare and tomato and olives green and black, and small golden pink mushrooms and cresses and beans. The waiter heaped my plate, and filled another glass with white wine. I drank half a glassful without a word, and began to eat. I was conscious of Richard Byron’s eyes on me, but he did not speak.

The waiters hovered beside us, the courses came, delicious and appetizing, and the empty plates vanished as if by magic. I remember red mullet, done somehow with lemons, and a succulent golden-brown fowl bursting with truffles and flanked by tiny peas, then a froth of ice and whipped cream dashed with kirsch, and the fine smooth caress of the wine through it all. Then, finally, apricots and big black grapes, and coffee.

Ah, apricocks and dewberries. They never fail.

But truly, isn’t that the most luscious, sensual scene? Aren’t you there, mouth watering? Haven’t you already decided that the provider of this voluptuous feast has to be the hero?

How much more powerful must it have been in 1955, when the book was first published. Many foods were still rationed in Britain. It was only ten years since the end of the War, with its austerity and British Restaurants. For the 1950s English woman, this idyllic meal (to say nothing of the plates that disappear as if by magic) must have felt as good as going to Cinderella’s ball herself.

And it still does the business today – for me and, I bet, for thousands of others. Which is why Hodder printed a new edition fifty years after that first publication.

Scrummy