Archive for the ‘Jenny’s week’ Category

Georgette Heyer: After the Plaque

Random jottings from the day by someone who felt privileged to be there, along with Georgette Heyer’s family – nephew Major General Jeremy Rougier, daughter-in-law and dedicatee of FALSE COLOURS Susanna, Lady Rougier and grandsons Nicholas Rougier and Noel Flint – friends, countless devoted authors and an extremely enthusiastic home team from Wimbledon.

To start with authorial trivia – we used this illustration from La Belle Assemblee as the back cover of the programme. It was kindly provided by Regency author Louise Allen, from her personal collection of prints. (I feel Miss Heyer would have approved.) We both suspect that it may have been the inspiration for Sophy’s dashing riding habit which she is wearing when she encounters Miss Wraxton and Charles in the Park and Miss Wraxton pointedly only compliments her horse.

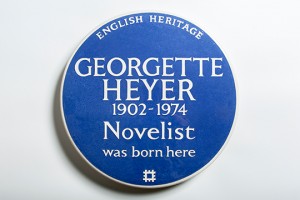

I promised that I would put up my take on events on the great day when Georgette Heyer and her birthplace received an English Heritage Blue Plaque. There is a great account of the history and purpose of Blue Plaques on their website . The very first person to be awarded one was Byron. I hope that would have pleasedMiss Heyer – and possibly made her laugh.

There is a truly excellent account of the unveiling — with the bonus of a little trip behind the scenes – by novelist Elizabeth Hawksley.

And then the 50 people who had attended retired to the Garden Hall at St Mary’s Church for tea and fizz, organised primarily by grateful author enthusiasts and the Romantic Novelists Association. We had an advisory panel of mainly Regency writers and Jen Kloester, Heyer’s biographer; I ran the Spreadsheet; while indomitable RNA stalwarts Jan Jones and Roger Sanderson made sure everyone was fed watered and had somewhere to sit. Remove balloons, replace flowers with much loved favourite Georgette Heyer books and you get the picture:

To interpolate another behind the scenes revelation here, the organisers did audition prosecco for the fizz role, on the grounds that is was light, summery and economical. But we rejected it in favour of champagne. Prosecco never achieved a mention in Heyer’s books and she deserved everything as handsome as we could make it. Though, as one gentleman reader pointed out, she mentioned champagne at least as often in connection with boot polishng as she did with quaffing. Maybe we should have had ratafia or orgeat .Yes, OK, I was OIC organisation and am still too close to it!

It was a terrific party – one of the nicest I’ve ever been to. People who had never met before were already chatting as they walked in through the door. There was huge satisfaction at the recognition of Georgette Heyer’s much loved work. For once, you felt, justice had been done. I heard favourite quotations on all sides – ‘I meant a well-bred horse’ ‘Hyde Park soldiers’ ‘a little bit on the go’ — and people who had never met before collapsed into shared laughter over a treasured Heyer moment. Above all it was warm, and friendly and fun.

Susanna, Lady Rougier, Maj Gen Jeremy Rougier, Dr Jennifer Kloester

photograph courtesy of Miranda Spatchurst

We were to have favourite readings over tea and it had fallen to me to choose them. As one of the world’s natural democrats, I had asked readers to tell me their favourite book, character and incident. Democracy is a terrible trap. People who wanted the same book, didn’t want the same incident or character. Cat herders of the world unite! In the end we had pieces from THE UNKNOWN AJAX, VENETIA and AN INFAMOUS ARMY. They were all splendidly read by actor Ric Jerrom and each book was the favourite of at least two people present. The company was spellbound. (‘Rapt,’ said my Dearest Friend and Severest Critic, in between buttling for Britain. He had just read AJAX, as his first ever Heyer, and had a lot to take in.) The announcement of VENETIA was received with a gusty sigh of pleasure.

The Pan Edition which was sitting on one of the tables

And yes, that was the scene Ric read, complete with dog.

In my Democratic Consultation on the readings, the winner by a fair margin was AJAX – people even wanted to hear the same scene – the splendidly theatrical final Pageant of Ajax, with Richmond drunk, Claud rising astonishingly to the occasion, and Lady Aurelia, a mere female with every one of her eleven earl ancestors at her back, dismissing the Officer of the Law in one crisp speech. I’ve always admired that scene but, read aloud, it was funny, exciting, humane and touching on so many levels. ‘Great writing,’ said Ric Jerrom, who hadn’t read her before. His is the masterly voice of Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin in the audio versions of Patrick O’Brian’s masterwork.

The big romantic title missing, of course, was the perennial favourite, THESE OLD SHADES. And – was it Fate? – the two people who had voted it their favourite, didn’t manage to make the tea. That coincidence gave me a frisson, I admit. Georgette Heyer married in St Mary’s Church in 1925, just six weeks after her father — mentor and greatest friend, who utterly supported and believed in her writing and whose work she critiqued and vice versa – had died suddenly after a game of tennis. It was a terrible loss. But he had already commented on THESE OLD SHADES , perhaps her most joyful book and unashamedly high romance, So the book was ready for publication, with his notes on her ms.

And following the reading of Colonel Audley’s encounter with Captain Kincaid of the 95th from AN INFAMOUS ARMY, Georgette Heyer’s nephew, Major General Jeremy Rougier, told us a brilliant story.

In 1964 he was a military assistant to a member of the Army Board (the top management of the Army) and they paid an official visit to Belgium. On a free afternoon they were taken on tour of the battlefield at Waterloo by the Professor of Military Studies at the Belgium Military Academy. Their guide was fascinating; he knew the position of every regiment at any time on both sides. “At about 3pm Napoleon was standing here – no, here,” he would say, moving 10 foot to record the precise spot. At the end he presented him with a signed copy of Georgette Heyer’s book and explained their connection. ‘He was as near speechlessness as a professor of military history can be,’ said the Major General. ‘He said, ‘This is the nearest to reality that one will ever come without having been there.” And he fainted!’

Allowing for the professor’s excessive sensibility — the storyteller’s dramatic licence was much appreciated — the readers of Georgette Heyer present were gratified but not really surprised.

For this was really a day in which people who knew her worth came together and celebrated that the word was getting out there. I had asked a number of them to give me their personal experience of reading her books. So I want to end this post with the very first reader to send me his contribution. It is a good representative of what we were all saying in our different ways.

‘As a young medical student, I came across ‘The Corinthian’. I think my brother discovered it first. I loved it; I thought it was hilarious and laughed no end. That set me off on reading Georgette Heyer books. I particular like the Regency stories with a nice plot, e.g. ‘The Reluctant Widow, ‘The Talisman Ring’, ‘The Unknown Ajax’, ‘The Toll Gate’ etc. Then I discovered some more historical novels, starting with ‘Royal Escape’ and ‘An Infamous Army’. Finally I came across ‘Envious Casca’ which set me off to reading all her detective stories.

‘In all of these different types of novel, the characterisation is so well done and reading them is such pleasure however often one has read them before. These are books to own and keep permanently on one’s bookshelves (or perhaps on Kindle?), not borrow them from the library. Whenever I am ill enough to retire to bed, I always take a Georgette Heyer book to bed with me to cheer me up.’

He emphasises something it is easy to forget. When I started to help with this celebration, I said to people who muttered about the time I was taking away from my writing to spend on it that a) it was a unique occasion and b) it was a small thank you to Georgette Heyer for a lifetime of interest and pleasure. I said it lightly – well, irritably sometimes — but it was true. A lifetime. And every reader I approached to write something, to help, to come along said the same thing.

So many lifetimes made happier by her books.

What a legacy. What a writer.

An Old Love

This week I went to the National Theatre’s production of She Stoops to Conquer. It broke my heart.

What I saw was a crass, shallow, crude peepshow of a play. Brutish Tony Lumpkin tells two wimpy London fops that his stepfather’s old fashioned house is an inn. So they turn up, give orders, treat their welcoming host as an over-familiar innkeeper and decide that his daughter is a barmaid.

This is a School of Big Brother production. The audience is invited to smack its lips lasciviously at the ensuing social and sexual fallout. Audience? Gloating voyeurs would be nearer the mark. I wanted to run away.

This is where I have to point out that the critics were all pretty keen — “a delight” The Independent ; “a mixture of wit and warmth”, The Guardian; ” fresh, spirited and blissfully funny” The Telegraph. And, to be fair, it is beautifully set and dressed.

Susan Kikoler is my guru in all things London theatrical. She goes to everything worth seeing. I consulted her. She hadn’t seen it but was not surprised at my report. She suspected as much from the tone of the reviews — apparently words like “boisterous” and ‘”spirited” are a give away for end-of-the-pier humour. She was not as upset as I was, though. ”It’s a difficult play. I never liked it,’ she confessed.

Ah. I went back to the text.

Susan is right, of course. Tony Lumpkin’s trick could be cruel. Restoration Comedy was full of heartless toffs tricking the unwary into betraying their inadequacies. Even Sheridan has his cold-eyed moments (Sir Peter Teazle’s realisation that his country wife has betrayed him can be heartbreaking, in the hands of the right actor.) But Goldsmith is different. His characters can be pretentious and silly but they are seldom completely self-deluded — even poor old Mrs Hardcastle knows, really, that she is not forty any more. Above all, they are generous. Even naughty Tony. At least I think so.

Now, I have always felt at home in the later Georgian period, tough though it could be (um, embarrasssing photo of self here)

and I have always loved these people.

I love the battle between countryfied ways and town polish. I love the real affection that Squire Hardcastle has for both his wife (struggling with advancing age and a cheerfully rebellious son) and his clever daughter, in spite of being a little too overtly the master in his own house. And, anyway, he isn’t; his servants talk back and he lets them; Mrs Hardcastle runs her own show and he lets her; he even compromises with Kate on her clothes – she can have Town furbelows for morning calls as long as she wears his preferred simple country dress for dinner time. I love Tony Lumpkin, a sort of Tom Jones in the making, a wild boy with his rural mates who knows he’s too immature to marry his cousin but is fair and generous to her in the matter of her inheritance. Above all, I love poor awkward, stammering, boastful, unwary Charles Marlow who, under the gentle encouragement of a well spoken inn maid, manages to find equilibrium between what he feels and what he can bring himself to declare to the world.

And what did I find at the National Theatre? For socially insecure young men, one of whom is a bit of a swot, we had cowardly fops (“beyond camp”, said my Companion gloomily but with justification, “pure Up Pompei”). Instead of the quicksilver mischief of Tony Lumpkin, we had the threatening leader of a gang of rural thugs. For that sound judge of true worth, lively Kate Hardcastle, we had a wind-up merchant channelling her inner pole dancer.

Nasty and not in the spirit of the play, which was first performed in 1773. Elizabeth Farren, the 18 year-old Kate who took the Town by storm in 1777, had a twenty year career playing Portia and Hermione as well as Lady Teazle and similar roles; then married the Earl of Derby. Her demurely pretty portrait was painted by Thomas Lawrence.

What hurts me is that this play is all the more poignant because Goldsmith himself was a mess. Young Marlow’s self knowledge and honest declaration at the end of She Stoops is hard won and it was Goldsmith’s battle, only with a happier ending. For Goldsmith was a gambler, a drunkard, a poor scholar (none of which applies to Young Marlow), a socially inept pock-marked pauper who never settled to a proper career. He busked his way round Europe, earning his bread by playing his flute, and, when he got back to England, was endlessly in debt, in spite of considerable success in his writing. He was vain, jealous and, in person, unpersuasive to say the least– Boswell records Goldsmith’s ill-judged exchanges with other members of The Club, in which he was constantly tied up in knots by the divine clarity of Johnson. Johnson, friendship at war with honesty, said of Goldsmith, “No man, was more foolish when he had not a pen in his hand, or more wise when he had.”

And that’s what I was missing in this production. The wisdom.

After their first disastrous exchange of tangled high sentiments (pure biography, I suspect, poor old Goldsmith!), Marlow gets away and Kate Hardcastle muses, “He has good sense, but then so buried in his fears, that it fatigues one more than ignorance. If I could teach him a little confidence …..” You think, that’s a sensible, affectionate girl who sees into the heart of things. They’ll do all right.

At the end, still thinking her a barmaid, Charles Marlow eventually realises, “What at first seemed rustic plainness, now appears refined simplicity. What seemed forward assurance, now strikes me as the result of courageous innocence and conscious virtue.” You want to throw your hat in the air and cry huzzah. He’s stopped caring what people think about him. He knows what he thinks about her. And what he feels. And he’s right. It is a triumph

So yes, I am in love again. Reading Goldsmith again. Going back to other eighteenth century writers. I suppose if it weren’t for last Thursday, I would not be. So, for that at least, dear National Theatre: thanks guys! I think.

Faberge Spring

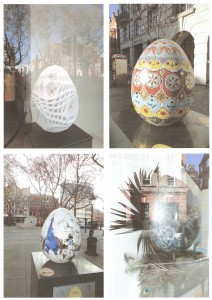

Clockwise from top left:

OVO in Hugo Boss’s window; Seraphina, to the left as you leave the station; Birth of Lilith in Peter Jones’s north west corner window; Peacock in his Pride, centre square, with Royal Court Theatre, the red brick building behind him.

What do you do on a bright, cold morning when it’s April Fool’s Day and you’ve written 1,000 words before breakfast? Me, I went for a walk and photographed eggs.

Not just any eggs, you understand. Sodding great artistic creations for this year’s The Fabergé Big Egg Hunt in aid of Action for Children and Elephant Family. I’ve been looking at these things with curiosity and pleasure for a few weeks but, up to now, I’ve only remembered to take my camera once and the eggs all move tomorrow. You can see them in Covent Garden, from Tuesday. So just for me — and anyone else interested — here are my neighbour eggs on their last day in Chelsea, photographed between 8.00 and 9.00 am 1 April 2012.

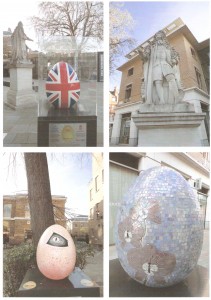

Clockwise from top left:

Union Jack, of which one aspect is not what you expect and very London– nice!; Jack’s neighbour Sir Hans Sloane, who said chocolate was really good for you, making him utterly statueworthy; Love and Flourish, Versailles blue and silver mosaic, the prettiest egg I’ve seen; Pandora, though I’d have called it Eye of Sauron, myself.

Goodbye, guys (except Sir Hans). Great to have known you!