Eva Ibbotson

I am so very sad to see from the Observer’s obit column on Sunday that Eva Ibbotson has died. She drew obits from The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph and the New York Times, quite rightly. All focused on her work as an accomplished children’s author. But they were sadly light on appreciation of her romantic novels for adults.

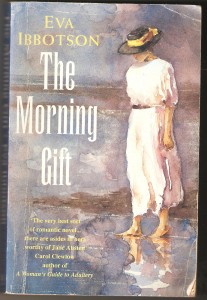

She did, of course, win the Romantic Novel of the Year with Magic Flutes in 1983, as the Telegraph noted. Um – recently re-issued, it has been given a new title, Reluctant Heiress, presumably by some pale eyed genius with a degree in Applied Bum-Numbing and no truck with allusion, ambiguity or intriguing the reader. Ibbotson was not impressed. She didn’t much like the new covers, either, which is why I have scanned in my own much loved, much read and just a tiny bit battered copy of my fabourite Ibbotson, below.

But she did more than win the UK’s main award for Romantic Fiction. She brought a fresh, idiosyncratic and deeply humane voice to romantic fiction. She was, you felt, a writer who knew what a happy ending was for.

Last year Anne Gracie (friend of mine and most excellent writer) interviewed Ibbotson on the always rewarding Word Wenches Blog. In her answers, Ibbotson said she thought of her books as presents for the reader and ‘not too much about my soul and the sunset’. She certainly gave her readers every last drop of satisfaction from the romantic entangling of her delicious, generous, healing heroines and her troubled heroes.

In the matter of heroes, even an enthusiast for romantic fiction like me has to admit that, sometimes, the modern author can short change him. He may end up not much more than an idealised loved object, dimly perceived through a fog of lust, sentiment and fag smoke. Not in Ibbotson’s novels. She knew her hero and she loved him, quite as much as she loved her heroine. Usually, he is not intrinsically glamorous; indeed there is a dash of nerd in most. Even my beloved Quinn in Morning Gift, has more than a hint of Gussie Fink Nottle about him. But when he applies that intensity, that seriousness, to the objective of his heart as well as to scholarship, he is breathtaking– especially as he struggles between what he wants, what he thinks the heroine wants and what it would be the right thing to do.

Ibbotson told Anne Gracie: ‘The kind of dichotomy between honour and passion is as old as the hills and I must say getting my heroes out of their dilemmas has sometimes not been easy.’ She always did but they travel a hard road before they get their reward.

Also, she loved her minor characters. As she told Gracie ‘the word minor hardly fits.’

I never forget the truly terrible scene from Countess Below Stairs, in which the washed-up and slightly disreputable Great Uncle is banished to his own rooms by an in-coming Eugenecist bride. After the heir’s marriage, Uncle will be condemned to stay upstairs, away even from the servants, who have known and cared for him all his life. He will be effectively a prisoner, with a nurse-jailer to ensure his good behaviour. Our heroine by now is breaking her heart for a man she cannot have. But she hauls herself out of her own misery, knowing that the humiliated old man can only be led back to some sort of peace through his music. So she persuades him to play a piano duet with her. Her hands are chapped and she’s out of practice. (She’s now employed as a housemaid.) His fingering has been ruined by rheumatism. So they sit down and play – and they do it, Ibbotson says, ‘Not well. Better than that.’

No, the word minor does not fit.

My own favourite of her novels is The Morning Gift, with its unlikely St George of a hero and its gloriously logical and slighty loopy heroine. Viennese Ruth, another refugee, not wholly in tune with Belsize Park or the stolid English, works everything out from first principles. As a result, she often gets them crashingly wrong. (By the way, for writers, this book contains a love scene so perfect that one despairs of ever writing one comparable, it is so heartfelt, so truthful, so sexy, with just the right spice of surprise and the faintly ludicrous.) But Madensky Square is perhaps more emotionally profound; A Company of Swans more magical; Countess both funnier and more of a fairytale. In all of them, though, Ibbotson has fantastic villains– smug, narrow minded people who throw their weight about because they can. You do not see for ages how decent people can possibly stand out against them. And then Ibbotson gives you the wonderful present of their come-uppance. They are trounced, usually by a divine alliance of the hero, the heroine and those life-enhancing not-minor characters.

But nothing I can say is as good as what Eva Ibbotson wrote herself. In that interview, Gracie also gave a link to a piece Ibbotson had written herself about what public libraries meant to the dispossessed refugees from Hitler’s Germany in 1930s Belsize Park. It was published in The Observer on July 9th 2006 and anyone who, like me, adores Morning Gift, will find familiar faces there. I’d quote from it but I don’t want to spoil it for you. It’s like a short story and it’s wonderful.

Please, please, please, read it here and see what a writer we have lost. But also enjoy!