Three Spies and a Kindle

Getting to know my Kindle better, I downloaded No 4 on the Spies and Thrillers chart, The Fulcrum Files by Mark Chisnell.

Set in 1936, it’s a story rooted in a period when people were desperate to believe that 1914-18 had seen the war to end all wars, when communism offered an apparently viable alternative way of organising society and the increasingly confident Soviet system was setting up networks to export it. In Britain, manufacturers were almost as reluctant as the government to believe that Germany was re-arming, as Mark Chisnell points out in his PS to this exciting story. It is also a time when pacifism was a vibrant issue and deeply divided friends and families.

Chisnell’s hero, Ben Clayton, is a decent upright human being, a bit of an outsider because his education is above his social class, and even more of a loner because, for profound personal reasons, he is a pacifist. The plot is convincingly riven with class warfare, bully boys and heroism, as our hero tries to investigate an accident with a newly designed mast in which his friend dies. He also tries to look after the widow, be straight with his girl friend (a lovely character) and keep his job. By the time he finds himself on the run in Germany, trying to keep ahead of the Gestapo, I couldn’t put it down. And there is some of the best writing about a chase at sea that I have read since The Riddle of the Sands, a book which our hero has read, marked, learned and inwardly digested. Riveting.

The Riddle of the Sands, published in 1903, is possibly the first spy story. I read a little John Buchan as a child and Fleming as I got older and could take it or leave the genre, frankly, though on the whole I preferred to leave James Bond. I didn’t find The Riddle of the Sands until I was in my twenties and living in Ireland.

Childers was a real child of empire who was converted to the cause of Home Rule and died gallantly for it in front of a firing squad in 1922. (His son was 4th President of Ireland 1973-74, succeeding his father’s friend Eamonn de Valera.) Childers was an enthusiastic sailor and his most famous story tells of a sailing holiday in the Baltic when a young chap from the Foreign Office (the proverbial Carruthers) is invited on a sailing holiday, with perhaps a little duck shooting, by an acquaintance, Arthur Davies. Davies, in fact, suspects that there is a secret German fleet being assembled off the Frisian islands, preparing to invade Britain and is out to prove his theory. Carruthers, the novel’s narrator is at first disconcerted, then flings himself into the venture and they end up sailing for their lives through the fog to warn England. Cracking stuff. Still on my bookshelf.

In an article in The Spectator in 1955 Ian Fleming criticised The Riddle of the Sands for a lack of believable villains. (So Drax, Goldfinger and Dr No are believable, I hear you cry). He also didn’t think it was thrilling enough! But then I’m not sure that Fleming understood suspense, as opposed to sadism, unlike Childers and Chisnell. But then, I’ve only managed to finish two.

James Bond is now identified by the movies rather than the books and, particularly,by the actor. It is said that the various incarnations reflected their times: currently Bond is an impassive hard man, played by Daniel Craig. Brosnan was sophisticated and witty; Timothy Dalton, sophisticated with a hint of a secret sorrow; Roger Moore a sophisticated comedian; George Lazenby not quite sophisticated — and then, first of all, there was Sean Connery. Fleming had envisaged Bond looking like himself (start with the sneer and work backwards, I guess) but he has a character say that Bond reminds her of Hoagy Carmichael. So this is what he wanted:

What he got was Sean Connery.

Serendiptiously, I came across a photograph of Connery as Pentheus in The Bacchae the Oxford Playhouse, in 1959, his pre-Bond days. (Michael David was Dionysos.) The photograph was taken by surrealist painter Oscar Mellor, who day-jobbed as a photographer with, I think you will agree, spectacular results. (A letter entitled You Muddy Fools appeared in the London Review of Books in 2002 on this self-effacing eccentric.)

Pentheus, of course, was torn to pieces by maddened women. For spying.

The Novel, the Witch and the Wardrobe

I was really grateful to Emma Lee Potter for the write-up on her blog of the panel of best selling novelists at last weekend’s Chipping Campden Literary Festival.But Fiona Walker’s advice made me wince: “Finish it. There are so many half-finished novels languishing in drawers.”.

Guilty, Guilty, So Guilty.

I have been asking myself what happened to relegate those poor stories to the drawer. Or in my case, the box file at the top of the wardrobe. Did I run out of steam? Drive myself down a blind alley and fail to find a way out? Realise they were crap and run away? Or did some bad fairy at my Christening give me what my friend Mary Jo calls the Tiffle Virus, so that I can never actually bring myself to stop tweaking, finish and say goodbye?

Well, the answer is, all of the above. But quite often the latter. Although sometimes I think she was not so much a bad fairy as an older sisterly sort of witch lurking somewhere in my subconscious who, after lobbing in eye of newt and other succulents, says, “Still a bit watery; needs something else; leave it and see if it comes to you.”

My only excuse is that, often, the witch is not wrong. When I push my way into the Wardrobe, I can see that she was absolutely right about my Knight of Ghosts and Shadows, a woman-in-jeopardy story with a hole in the plot you could drive a London bus through.

Or Someone Else’s Business which was about three books in one. Worse, the heroine fancied the wrong man and wouldn’t stop, no matter what I did. “‘You’ll have to kill him,” said my friend Annie, best seller, dearest friend, severest critic and all round bootfaced sadist when it comes to her own characters. But by then I was in love with him too and I couldn’t bring myself to do it.

BUT

… for at least some of these Wardrobe-bound stories, their time will come. If you’re a writer, never forget that.

A case in point – sometimes in the 90s I wrote a book for Harlequin Mills & Boon with a waif heroine. They turned it down, saying that waifs were out of favour. Presumably they were too kind to say that the story was only half cooked. Heroine fine. The hero had the charisma of a cornflake packet.

That’s what I discovered when, scrolling forward ten years, HMB were looking for a ms urgently to fill a slot. Only by then I had a new hero, a real hero, waiting in my imagination. Helped by some judicious prodding from fab editor Kate Paice, I wrote 25,000 new words in a week. And it worked. The Cinderella Factor is now one of my favourites.

So the moral I deduce is: Finish the Damn Book, fine. But don’t tear your hair out if it needs to rest a bit first. The same is true of the finest burgundy.

Just go Finish Another Damn Book in the meantime.

An Old Love

This week I went to the National Theatre’s production of She Stoops to Conquer. It broke my heart.

What I saw was a crass, shallow, crude peepshow of a play. Brutish Tony Lumpkin tells two wimpy London fops that his stepfather’s old fashioned house is an inn. So they turn up, give orders, treat their welcoming host as an over-familiar innkeeper and decide that his daughter is a barmaid.

This is a School of Big Brother production. The audience is invited to smack its lips lasciviously at the ensuing social and sexual fallout. Audience? Gloating voyeurs would be nearer the mark. I wanted to run away.

This is where I have to point out that the critics were all pretty keen — “a delight” The Independent ; “a mixture of wit and warmth”, The Guardian; ” fresh, spirited and blissfully funny” The Telegraph. And, to be fair, it is beautifully set and dressed.

Susan Kikoler is my guru in all things London theatrical. She goes to everything worth seeing. I consulted her. She hadn’t seen it but was not surprised at my report. She suspected as much from the tone of the reviews — apparently words like “boisterous” and ‘”spirited” are a give away for end-of-the-pier humour. She was not as upset as I was, though. ”It’s a difficult play. I never liked it,’ she confessed.

Ah. I went back to the text.

Susan is right, of course. Tony Lumpkin’s trick could be cruel. Restoration Comedy was full of heartless toffs tricking the unwary into betraying their inadequacies. Even Sheridan has his cold-eyed moments (Sir Peter Teazle’s realisation that his country wife has betrayed him can be heartbreaking, in the hands of the right actor.) But Goldsmith is different. His characters can be pretentious and silly but they are seldom completely self-deluded — even poor old Mrs Hardcastle knows, really, that she is not forty any more. Above all, they are generous. Even naughty Tony. At least I think so.

Now, I have always felt at home in the later Georgian period, tough though it could be (um, embarrasssing photo of self here)

and I have always loved these people.

I love the battle between countryfied ways and town polish. I love the real affection that Squire Hardcastle has for both his wife (struggling with advancing age and a cheerfully rebellious son) and his clever daughter, in spite of being a little too overtly the master in his own house. And, anyway, he isn’t; his servants talk back and he lets them; Mrs Hardcastle runs her own show and he lets her; he even compromises with Kate on her clothes – she can have Town furbelows for morning calls as long as she wears his preferred simple country dress for dinner time. I love Tony Lumpkin, a sort of Tom Jones in the making, a wild boy with his rural mates who knows he’s too immature to marry his cousin but is fair and generous to her in the matter of her inheritance. Above all, I love poor awkward, stammering, boastful, unwary Charles Marlow who, under the gentle encouragement of a well spoken inn maid, manages to find equilibrium between what he feels and what he can bring himself to declare to the world.

And what did I find at the National Theatre? For socially insecure young men, one of whom is a bit of a swot, we had cowardly fops (“beyond camp”, said my Companion gloomily but with justification, “pure Up Pompei”). Instead of the quicksilver mischief of Tony Lumpkin, we had the threatening leader of a gang of rural thugs. For that sound judge of true worth, lively Kate Hardcastle, we had a wind-up merchant channelling her inner pole dancer.

Nasty and not in the spirit of the play, which was first performed in 1773. Elizabeth Farren, the 18 year-old Kate who took the Town by storm in 1777, had a twenty year career playing Portia and Hermione as well as Lady Teazle and similar roles; then married the Earl of Derby. Her demurely pretty portrait was painted by Thomas Lawrence.

What hurts me is that this play is all the more poignant because Goldsmith himself was a mess. Young Marlow’s self knowledge and honest declaration at the end of She Stoops is hard won and it was Goldsmith’s battle, only with a happier ending. For Goldsmith was a gambler, a drunkard, a poor scholar (none of which applies to Young Marlow), a socially inept pock-marked pauper who never settled to a proper career. He busked his way round Europe, earning his bread by playing his flute, and, when he got back to England, was endlessly in debt, in spite of considerable success in his writing. He was vain, jealous and, in person, unpersuasive to say the least– Boswell records Goldsmith’s ill-judged exchanges with other members of The Club, in which he was constantly tied up in knots by the divine clarity of Johnson. Johnson, friendship at war with honesty, said of Goldsmith, “No man, was more foolish when he had not a pen in his hand, or more wise when he had.”

And that’s what I was missing in this production. The wisdom.

After their first disastrous exchange of tangled high sentiments (pure biography, I suspect, poor old Goldsmith!), Marlow gets away and Kate Hardcastle muses, “He has good sense, but then so buried in his fears, that it fatigues one more than ignorance. If I could teach him a little confidence …..” You think, that’s a sensible, affectionate girl who sees into the heart of things. They’ll do all right.

At the end, still thinking her a barmaid, Charles Marlow eventually realises, “What at first seemed rustic plainness, now appears refined simplicity. What seemed forward assurance, now strikes me as the result of courageous innocence and conscious virtue.” You want to throw your hat in the air and cry huzzah. He’s stopped caring what people think about him. He knows what he thinks about her. And what he feels. And he’s right. It is a triumph

So yes, I am in love again. Reading Goldsmith again. Going back to other eighteenth century writers. I suppose if it weren’t for last Thursday, I would not be. So, for that at least, dear National Theatre: thanks guys! I think.

Jack Reacher, Closet Nerd?

I have a confession to make. I can’t take most currently popular crime novels. It’s a genre I’ve always loved and it makes me sad.

Crime novels, says PD James, are about the restoration of the social order. They are about justice. Now I have a passion for justice and an appetite for murder in a story. I relish following a character over the tipping point where the functioning social being goes out into the dark alone to kill. But, but, but …. I can’t be doing with voluptuous nastiness, even when it’s very well written. Maybe especially when it’s very well written.

Take an example. I read the Millenium Trilogy in one bound, as it were. Was fascinated by the characters and the ideas but the violence was such that I really had to brace myself to read the second in the series. I’m glad I carried on through book 2 and then finished The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest. But I’m pretty sure I couldn’t take it again. Nastiness like that gets into my dreams.

Maybe I’ve overdosed. And not just on Stig Larsson.

Which is why I have always puzzled over my willingness to pick up another Jack Reacher novel. Some (though not all) of Lee Child’s murderers are sadists. There is a high body count. Violence is not shirked. Reacher, of course, is a hero– a career soldier who retires and declutters his life of everything, house, books, relationships, laundry. (Possibly a touch of wish fulfilment for me there, I thought.) He solves problems beautifully. Restores justice. Moves on. A hero, certainly. But my hero? Why?

And then I read Killing Floor and realised wherein lies his attraction. He is my soul mate. He believes in apostrophes. Hell, he deduces clues from apostrophes.

Reacher and a fellow investigator are looking for what Hitchcock called the McGuffin. They have found a list but so far have drawn a blank. Then Reacher has an idea.

‘You recall the second to last item?’ I asked him.

‘Stollers’ garage,’ he said.

‘Right, ‘ I said. ‘But think about the punctuation. If the apostrophe was before the final letter, it would mean the garage belonging to one person called Stoller. The singular possessive they call it in school, right?’

‘But?’ he said.

‘It wasn’t written like that,’ I said. ‘The apostrophe came after the final letter. It meant the garage belonging to the Stollers. The plural possessive. The garage belonging to two people called Stoller. And there weren’t two people called Stoller living at the house out by the golf course.’

Soul mates, I told you.

Lucky 7: From Work in Progress

Social Media keep throwing me new challenges — or a curveball (‘a deceptive pitch, in which the ball dives downward as it approaches the plate) depending on your point of view. Today Janet O’Kane twittertagged me to take part in Lucky 7: Seven lines from new works.

Rules are:

- Go to page 77 of your current MS or WIP (simples)

- Go to line 7 (got that)

- Copy the next 7 lines, sentences or paragraphs (um . …) and post them as they’re written (runs away screaming)

- Tag 7 more writers and let them know. ( glug)

So here goes with the Work In Progess. I’m not going into context or character thumbnails. As Shakespeare said, good wine needs no bush. And if it ain’t good, well it’s a draft and, anyway, John Wayne does it for me— Nevah apologaaaahse; issa sarna wikn’ss. So I’m delegating the PR to my characters. Off you go, guys:

‘The Countess was a Pre-Raphaelite – well a fellow traveller, anyway – so our Paradise Garden is a mish mash of Garden of Eden and the Thousand and One Nights.’

‘Gabby –’

‘She wanted a cloister as well but her husband put his foot down.’

‘I’m not surprised,’ muttered Marek. ‘Gabby –’

‘Apple trees for the Tree of Knowledge, of course, and roses for the Persians– and the Victorian bulldozer in the picture was to build a mini canal because water symbolises life.’

‘Gabby,’ said Marek very loudly, ‘shut up.’

Now you may now want to go and read, or even listen to, something classy. SYLVESTER, a book in which the palpitating writer finds just how bad it can get, is read by (be still my beating heart) Richard Armitage. You can even hear a sample on Naxos’s website:

And Friends, forgive me, I’m tagging you because I want to know what you’re writing now. But I don’t think you get struck down by palsy or even writer’s block if you don’t come up with 7 lines. The luck has already happened and it’s all on my side, knowing you and your lovely books . . .

Faberge Spring

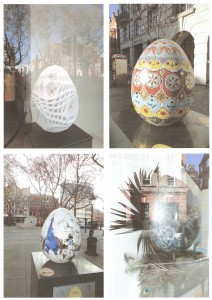

Clockwise from top left:

OVO in Hugo Boss’s window; Seraphina, to the left as you leave the station; Birth of Lilith in Peter Jones’s north west corner window; Peacock in his Pride, centre square, with Royal Court Theatre, the red brick building behind him.

What do you do on a bright, cold morning when it’s April Fool’s Day and you’ve written 1,000 words before breakfast? Me, I went for a walk and photographed eggs.

Not just any eggs, you understand. Sodding great artistic creations for this year’s The Fabergé Big Egg Hunt in aid of Action for Children and Elephant Family. I’ve been looking at these things with curiosity and pleasure for a few weeks but, up to now, I’ve only remembered to take my camera once and the eggs all move tomorrow. You can see them in Covent Garden, from Tuesday. So just for me — and anyone else interested — here are my neighbour eggs on their last day in Chelsea, photographed between 8.00 and 9.00 am 1 April 2012.

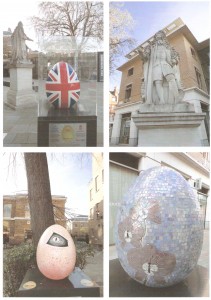

Clockwise from top left:

Union Jack, of which one aspect is not what you expect and very London– nice!; Jack’s neighbour Sir Hans Sloane, who said chocolate was really good for you, making him utterly statueworthy; Love and Flourish, Versailles blue and silver mosaic, the prettiest egg I’ve seen; Pandora, though I’d have called it Eye of Sauron, myself.

Goodbye, guys (except Sir Hans). Great to have known you!

Stephen Jenn, Sorceror

Stephen Jenn was an actor, a hero and my friend. Yesterday I went to his funeral.

It was in the Actors’ Church, St Paul’s in Covent Garden. Inigo Jones’s lovely building, one of Stephen’s favourite places, was full of spring light.

On his coffin there was rosemary for remembrance. So today I am remembering.

I saw Stephen act long before I knew him. He was Silvius, the romantic shepherd in As You Like It in the Open Air Theatre in Regent’s Park. I never forget the soft summer night, the heartbroken poetry, that wonderful voice. It got right into me, into the core and sinews of my imagination. And it’s still there.

Though, to be fair, it took me a while to realise that the Superior Being taking English Gentleman’s Tea at 4 o’clock on the dot was my heart-stopping shepherd. Stephen scoffed when I told him I’d seen him all those years ago. So, to prove it, I dived into my precious store of programmes of plays I really, really loved– and produced the evidence.

Stephen put aside his hot buttered toast, third cup of tea and umpty um years and turned into the young unrequited lover, telling the sophisticates around him ‘ what, ’tis to love’:

It is to be all made of fantasy.

All made of passion, and all made of wishes

All adoration, duty, and observance,

All humbleness, all patience and impatience,

All purity, all trial, all obedience,

And so am I for Phoebe.’

And yes, the Voice was still magic.

But then, I already knew about the Voice, whether he was Chatting to the Telephone Salesman (he scored if he got them to ring off first), persuading my nervous cat to have his tummy tickled, Rebuking Radio 4 (he wasn’t usually up for the Today programme but he would have a good old argument with PM, not to mention Front Row) or reciting poetry as he went about the house. More than once I went into the kitchen to find him telling the kettle sorrowfully:

Alas, ’tis true, I have gone here and there

And made myself a motley to the view,

Gored mine own thoughts, sold cheap what is most dear –

Mostly it was Shakespeare, occasionally Donne or Marvell; often plays that I didn’t know. Then I would get not only a one-man performance but programme notes and a potted history as well. ( I’m not surprised that he was much in demand as a visiting professor in the USA; the lectures were spellbinding.) And once, fabulously, after I’d enthused about a Toccata of Galuppi’s, he seized my Collected Works and we had an impromptu evening of Robert Browning.

Often he made me weep with laughter. Filming Cleopatra, as Temple Priest, he carried the basket of asps to the queen. And when she lifted the wicker lid, it was free from rubber snakes and, indeed, anything else except a card on which someone had helpfully written, ‘Hiss’.

Very soon after we met, I went to see him as Mephistopheles in Marlowe’s Faustus at the Young Vic. I knew he’d been ill and this was his first attempt at a big role since his treatment. He wasn’t sure about remembering the words. He needn’t have worried. He said them as if he had just that moment had the thought. In his hands Mephistopheles was clever, sophisticated, playful, wickedly seductive — and yet I can still hear the huge weary despair in ‘Why this is hell, nor am I out of it.’ I still feel the shock, too, as he turned from a sober student in spotless ruff, black robes and a cap, to an agonised shapeless thing, except for the arching throat and silently screaming mouth. Pure Hieronymus Bosch.

At supper afterwards — a long time afterwards, he was a hero who took his make-up off at glacial pace — he gave me a detailed explanation of how he effected the transformation from scholar to horror. I think he would have jumped on the table at La Barca to demonstrate if he hadn’t twigged by then that I have a very low embarrassment threshold.

And not for a moment, then or ever afterwards, did he even hint that his acting career was already into injury time and he knew it.

Stephen was ferociously determined not to be a victim. If his medication slowed him down, well then he would take life at an imperial tempo, letting the day wait upon him. As his left side weakness became more and more apparent, he simply acted his way through it. In the end, even class acting like his could not keep that heroic frame upright. Then there came the wheelchair, the carers and, worst of all, silence. But even then he sometimes had that wicked glint of laughter, when you said something that caught his fancy. His courage humbled me. A true hero.

But I don’t remember him sadly. I remember him with awe and laughter and gratitude and much tenderness.

One Christmas he took exception to my tatty fairy on the top of the Christmas tree. ‘Give her a new dress,’ he said. ‘Something with a bit of style.’ I brought out my box of scraps and he chose white silky stuff, purple felt, purple braiding and an old broken chain of seed pearls. I’m no dressmaker but I cobbled together something that looked all right. Well, from the front at least. Stephen anchored her to the top of the tree, stood back critically, and then gave his huge, wonderful grin. ‘Duchess of Malfi to the life,’ he said.

And then, in the firelight and the beat up Christmas tree lights, he launched into Prospero’s great speech:

These our actors

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air,

And like the baseless fabric of this vision.

The cloud capped towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yes, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind.

It brought the hair up on the back of my neck then. It still does. I was very privileged.

Ave atque vale, magister.

Surprise and Delight – book review

A few weeks ago a friend sent me a novel by an author new to me, Kerry Greenwood. ‘I thought it would make you smile,’ she said.

She was right. It did. And think. And feel. And count my blessings. And want to bake something.

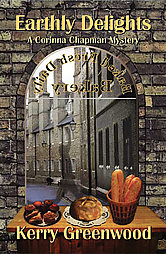

Earthly Delights is formally a detective story but absolutely nothing about it is conventional. It’s set in Melbourne, in an idyllic corner of the city where the small shopkeepers are eccentric, have a working community and help each other out. The narrator heroine is an artisan baker. She lives in a Roman-themed apartment block called Insula, complete with fountain in the entrance hall and blissful rooftop garden. Cosy crime meets pure fantasy, you might say.

Except that it’s not that cosy – OK the cats, are pretty cosy; I’m particularly taken with the dusbtin moggies on the bakery strength as the Mouse Police – but this is a world where bad things are happening and, anyway, none of these characters comes without baggage, some of it pretty nasty. The hero in particular is a mystery: sex on a stick, but also unsettling. Neither the heroine nor the reader is quite sure what she is signing up for.

But, oh, that heroine. She is, quite simply, bliss. Corinna Chapman has escaped the rat race to bake professionally but she likes figures. She was a happy accountant, she just hated the mad rush-to-the-office and the life that goes with it. Every day, as commuters come in to her shop to buy their breakfast muffins, you can feel her sympathy and her delight that the poor deluded fools have a moment of pleasure in their tense, nasty, money-making days. Apart from that, she is creative, warm, practical, kind, affectionate and so very, very, sane.

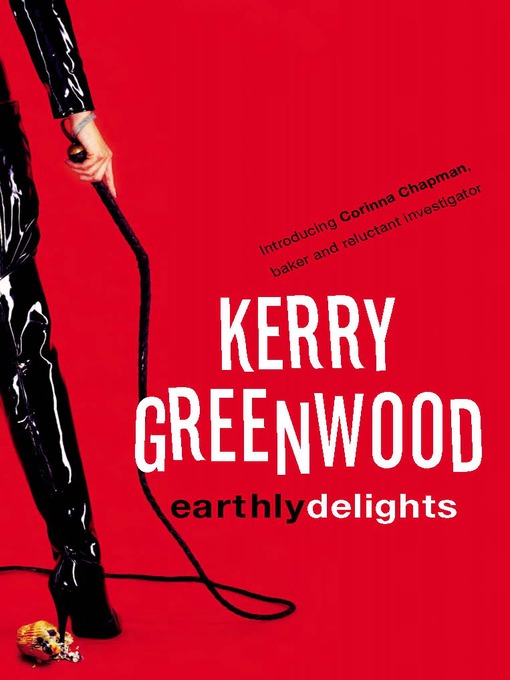

Add that it is beautifully written, deeply civilised, sprinkled with unpretenious reflections that set you thinking and just a touch kinky, and you will see that this book is a real original. To illustrate my point: there are two covers on line. Both fit the story. Like the Goddess Hera, Corinna has a domestic aspect and a distinctly dangerous one. And she’s pretty sexy, too.

Buy it for someone you love this Chrismas. Better read it first, though.

Enjoy!

November

November was – well – busy. I didn’t get as much done as I meant, especially writing, but I sure did a lot.

Some was lovely – a magical walk in crisp morning air along the sunlit River Dee with dear friends; some was grim (the economic news, what can I say?); some was panic-inducing. But then there were hero plumbers to rescue me from the latter (a Terrible Leak) so even that was not all bad.

I’ve also been trying to train myself to take photographs. This is a big step for one who hasn’t had a camera since she was at school. @lizfenwick guided the purchase. I’ve been circling the thing slowly ever since, in case it explodes on contact with inexpert hands. I was surprised to find, on first attempting to photograph, that a proboscis shot out. Made me jump a fair height, I admit. But then I realised, it had quite a friendly chirring noise, even if everything else was alien. So in November I got a bit braver. The results aren’t great but, oh boy, they make me smile.

So, in addition to leaks and disasters, November gave me:

winter sunsine, golden tree with London Taxi Cab

Unseasonable jasmine outside my door, with scent

and Friend . . .

poor sad cat left all alone while She gallivants, nobody love him and his paws are cold

And if I may just write a story about a Hero Plumber, too.

Goodbye November. You were a valuable learning experience.

The Malvolio Syndrome

‘You are,’ says Malvolio in Twelfth Night to a raggle taggle bunch of rogues and roisterers, ‘lesser things. I am not of your element.’

For centuries, one lot of writers has been saying that to another lot of writers. Mind you, the ratings change a bit over time. Jane Austen has been promoted to the Premier League since her own day.

But Looking Down The Nose seems to be an occupational hazard of The Writer, witness the bunch of worthies who this year felt that the Man Booker had gone too down market– become too readable, apparently– so proposed a new, better prize. (For unreadability?) At the time I suggested it should be called the Malvolio. On reflection, however, I feel it would be better named after a Superior Writer, even if a fictional one. The Lady Florence Craye Commemorative Cup appeals.

But to come to my own area, romantic fiction. Allegedly it rots the brain and ruins the syntax. Indeed, there is a school of thought which claims that it is written and published by cynics, aiming it squarely at what our American Cousins call Trailer Park Trash. And there always has been.

Being, I freely admit, of the rogue and roisterer persuasion, it ill behooves me to look down the nose at any writer, be he critic, commentator or pure Malvolio. However, I do think that defining romantic fiction as the purview of certain class or IQ band is very old and is all about us not liking bits of ourselves, for whatever reason. Thus it can be a bit of a trap, both for commentators and those of us who actually write the stuff because we like reading it.

The redoubtable Alex Stuart, one of the RNA’s co-founders and author of 4 serials a year, many of which were subsequently published by Mills & Boon, certainly worried about ‘the impressionable reader’. By that, she seems to have meant shop girls and typists, a class to which she emphatically did not belong herself.

This made her somewhat conflicted. On the one hand she wanted more respect for romantic fiction, on the other she did not set her claims too high. In a letter to the Editor of The Woman Journalist in spring 1960, she wrote: ‘Our books may be unrealistic and have happy endings, but they are almost all well written and they are read, in serial as well as book form, by hundreds of thousands of women and young girls who – if my fan mail is anything to go by – derive real pleasure from them.’

Um– is it just me, or do you find a faint hint of surprise in that ‘real pleasure’? Sad, isn’t it?

Yet George Orwell, in his Hampstead bookshop in the thirties, saw exactly who it was who read bestselling romantic novelist Ethel M Dell. (‘When Mrs Dell speaks, an Empire listens’ claimed her publisher.) And it was ‘women of all kinds and ages and not, as one might expect, merely wistful spinsters and the fat wives of tobacconists.’ Still, he does say that Dell’s books were read ‘solely by women’ which clearly puts them way, way down in the pecking order.

And then there was Georgette Heyer, crippled by terminal self-deprecation, as Jennifer Kloester’s stunning new biography makes clear. Oh, for God’s sake woman, you’re still in print 90 years after your first book was published. A few years ago you were the most borrowed author under PLR. Don’t let the Malvolii play mindgames with you. Be proud.

Personally, I have a soft spot for Lady Mary Wortley Montague, blue-stocking, literary duellist, patron of Henry Fielding and no slouch in either the travel, scholarship or sheer snottiness departments.

Here she is, telling it like it is about Samuel Richardson, author of Pamela. Having said sniffily that he wrote for chamber maids, she is brave enough to come clean: ‘I heartily despise him, and eagerly read him, nay sob over his works in a most scandalous manner.’

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu rocks.